I sat at my desk with a notepad and pen, trying to build a timeline—dates, names, lives lived and lost. I’d gone back in time out of order which increased my confusion. The past felt like a machine I was trying to coax back to life, only the gears didn’t quite mesh. The pieces didn’t fit.

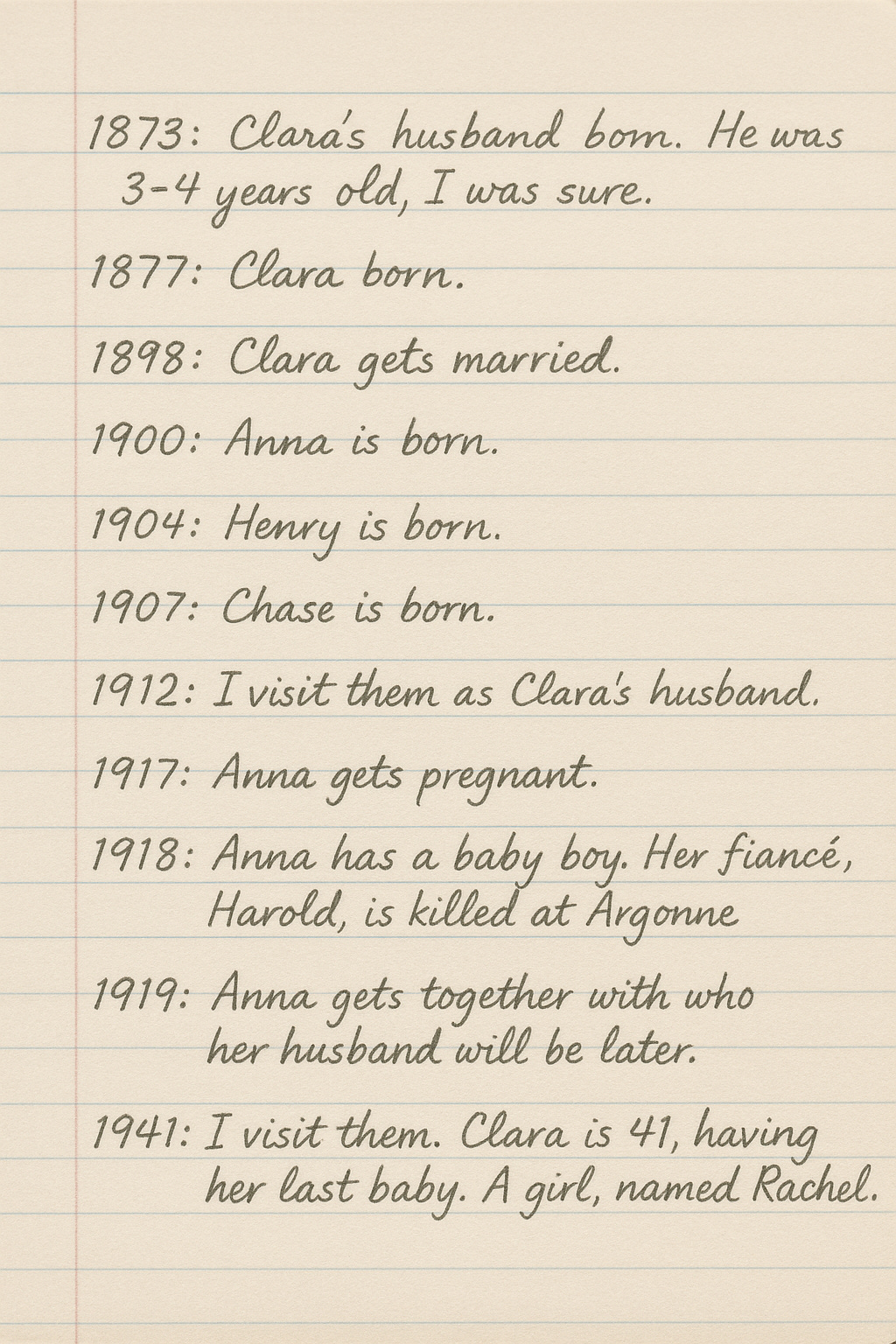

Most of the dates were guesses. Clara was about 35 when I first met her in 1912. Her husband—who I had once been—must’ve been older. I guessed 39. He likely died sometime between 1919 and 1941.

The only last name I knew was Whitney—but no first name, and likely not Clara’s family name. And not Anna’s first son’s name, unless Mr. Whitney adopted him later, which was possible.

I took the next day off and spent the morning at the courthouse, digging through deeds, birth records, marriage certificates, and death notices—just trying to find enough puzzle pieces to glimpse the picture.

That’s when I found her. One family member still living nearby: Rachel—the little girl I’d held in 1941. It was the summer of 2002, which meant she was sixty-one, a year or two older than my parents.

She likely hadn’t retired. And I hadn’t bought it from her—I’d bought it from a college professor who’d since left the area. So the house had been sold outside the family at some point before me.

Rachel Beal, as it turned out, had moved to—fittingly—Beals Island, off the coast of Maine, connected to Jonesport by a narrow arched bridge. Six hundred people lived there. She was one of them.

I found her in the white pages and called that afternoon.

“Hello?” she answered.

“Hi, Rachel?”

“This is she.”

“You don’t know me, but my name is Stephen Anthony. I live in the house in Marshfield where your grandmother lived.”

“You bought Nana’s house on the Ridge Road?”

“We did, about five years ago.”

“I haven’t seen the old place in years,” she said. “Is it still in good shape?”

“We’re improving it. The tin ceilings are still great. We pulled up asbestos tiles in the kitchen and found the original hardwood. The local guy was shocked it was there.”

“Really!” she said. “I don’t remember hardwood in the kitchen.”

“Probably covered up in the forties or fifties,” I said. “But it was there when you were born.”

“It was? Did you know I was born in that house?”

“I did hear that,” I said.

A small lie. I hadn’t heard it. I’d been there. Well—not me, exactly. But my mind had.

And suddenly, I wanted a cigarette. I hadn’t in years.

“Mrs. Beal,” I said. “I’m trying to piece together the history of the house. Your mother, your grandmother. Maybe her parents. Anyone from your family who lived there.”

She went quiet.

Then she said, “My older brother Randall probably would’ve inherited it, had he lived.”

“I’m sorry, Rachel. What happened?”

“Normandy,” she said.

That was all she needed to say.

There was a silence.

Then I had a thought.

“Was Randall your oldest brother?”

“Yes.”

“So… he was your half-brother.”

Another pause.

“Nobody knows that,” she said.

“I found some records.”

“Then you know. My mother lost her fiancé in World War I. She was already pregnant when he died. I guess it’s lucky for me—if he’d come back, I wouldn’t exist. But she always carried him with her. Even more after my father died. Then she lost her firstborn, his son, in World War II. He was twenty-six.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

“It was a long time ago,” she said. “It’s hard to admit, but I barely remember him. I was young.”

She paused again.

“But what really devastated her was losing my nephew in Vietnam.”

“Nephew?”

“Her high school boyfriend was Harold. As I said, he died in World War I. Then his son died in World War II. And then his son died in Vietnam.”

“My God,” I said. “Three generations—lost to war.”

“Momma died two years after we lost Kevin. Same year we lost my youngest brother. I think she died of a broken heart.”

“What year?”

“1968. Kevin was just a boy. If it hadn’t been for my father and brothers stepping in…”

“So Randall was the son of Anna and Harold?”

“Yes.”

“And Randall’s son was Kevin.”

“Yes.”

“Okay,” I said. “I know this is hard to talk about. I appreciate your time. Say—my wife asked if you’d like to come see the house sometime. Maybe coffee next weekend?”

“I’d love to see Nana’s house,” she said. “Can’t this weekend, but next works.”

“That would be great,” I said.

But I jumped through time before it happened.

“Hey, did you fall asleep?”

I woke up.

“Huh?”

“You did! And here you’re supposed to be making sure I stay awake.”

“Sorry,” I said.

It’s strange to wake up without going through the period of trying to get your eyes to adjust. I simply opened my eyes, and I was there.

Sitting next to me was a young man, still in high school, maybe sixteen years old.

“It’s okay. I know what I’m doing,” he said.

He was driving a car. A 1941 Packard 120 in green. It was fraying at the edges. My old car.

Sort of.

It had been owned by Jonathan Whitney, who I had lived as in both 1919 and 1941.

“Remind me, what year it is,” I said.

“Come on, Uncle. I know you’re old, but you’re not that old.”

“I’m just trying to figure out how you grew up so fast,” I lied.

“Well,” the boy said, “It’s 1958 and I’m fifteen, and you’re twice my age.”

Sure, I thought. I could be thirty.

I watched the road signs trying to pick something out. Eventually, I saw one—Route 1A.

We were between Ellsworth and Machias, Maine. Just then I saw the sign for Milbridge in nine miles. We were heading back to Machias. A little over a half-hour ride.

“Hey, there’s got to be a gas station in Milbridge, right?”

“Yeah, but I filled up in Ellsworth.”

“I want to stop for a drink and some smokes.”

“Smokes? I thought you quit?”

“You don’t know everything about me,” I said, grinning.

Then it dawned on me to check my pockets to see if I even had money to buy cigarettes. Yep. Wallet intact. I pulled it out to look. It contained sixty-seven dollars. It seemed like a lot of money for 1958. I wondered what I did for work. Then I spied the driver’s license and pulled it out.

I was Mark Whitney, born February 5th, 1927.

I was Anna’s son.

I was Rachel’s brother. I had another brother, Peter, who was older. And my half-brother Randall, the oldest of us, had been killed on D-Day in Normandy.

The driver’s license gave me an idea.

“So about your license—” I just let it hang in the air.

“I’ll pass it this time,” he said. “It was just a dumb mistake.”

“Yeah,” I said. “So you have your driver’s permit on you, right?”

“Course,” he said.

“Let me see it,” I demanded.

He looked at me, side-eyed. “What? Don’t believe me?”

“I do. I just haven’t seen what they look like. Just curious.”

He dug into his back pocket and flipped me his wallet, trusting me like I really was his uncle.

I pulled out the permit.

Kevin Whitney. Born December 6th, 1943.

I caught my breath.

Anna’s fiance Harold—killed in action at Argonne in World War I. Her son Randall, conceived on her engagement night, Christmas 1917. Killed in action on D-Day in World War II.

This kid was going to die in Vietnam.

Her grandson. Three generations. How could I let that happen? Could I even stop it? Should I even stop it if I could?

It was 1958 now. He would be dead in ten years.

The real woman I had somehow loved in these hallucinatory dreams was going to lose three men to war.

No. I corrected myself. She already has.

“You okay, Uncle?”

I looked over at him, tears in my eyes, and handed back his wallet.

“History has a way of mocking you,” I said.

“I don’t understand,” Kevin said.

“I know.”

I had seen Anna at twelve years old, again at eighteen years old, and a third time at forty-one when I spent four nights with her and her baby.

When I saw her that night, at fifty-eight years old, I was shocked by two things: first, how tired she looked; second, how beautiful she still was.”

“Hi, Mom,” I said as I stepped inside the house.

“Hi, Mark,” she said, stirring a pasta sauce on the stove in the house that would be mine in forty years.

I walked over, kissed her, and gave her a big hug.

It’s okay for sons to do that, right?

“Oh, my!” she said, dropping the spoon. “Everything okay?”

“Yeah—Ann—Mom,” I said.

She gave me a strange look.

“What?” I asked.

“Your eyes look different,” she said, taking a step back from me. “I—It’s very strange. A feeling of deja vu.”

I smiled at her but said nothing more about it. Just happy to be there with her.

I was shocked when Anna’s mother, Clara, shuffled into the room. Now slightly over eighty, she no longer moved well. But she still had a great appetite.

So did I. Anna’s meatballs were fantastic.

Later, Anna stepped outside to the porch.

“I thought you quit smoking,” she said as I pulled the pack out of my pants.

“I did,” I said. “I suppose I will again someday.”

“Everyone quits eventually,” she said.

Then she paused and looked in my hand.

“Lucky Strikes? I thought you smoked Marlboro? Your dad smoked Luckies.”

“Where is dad?” I asked.

“Bangor,” she said. “I thought you knew that?”

“Yeah, sorry,” I said. “I forgot.”

“You forgot? What is going on, Mark?”

“Sorry, just feeling a little displaced.”

“You look displaced,” she said. “And I’ve seen that look before. I saw it on your father, twice. My dad once. It scares me.”

“What do you mean?”

“I—I can’t explain it,” she said. “Like someone different is behind the eyes maybe?”

“That’s weird, Mom,” I said, trying to reassure her.

“You’re telling me!” she said. “Sometimes I feel like sorrow is waiting for me. Just out of reach, like a letter I haven’t opened yet.”

I stood there, looking at her, knowing she would be dead in twelve years, and it broke my heart.

They would all be gone. All of those people I had met. Clara’s sons, Henry, Elliott, Chase. Jonathan, my father, who I had also been twice. He was gone. Anna was gone. They were all gone in my world.

It was utterly unbearable.

“You okay?” Anna asked.

“Just a lot going through my mind. A lot of sorrow.”

“I understand all too well,” she said, putting her arm around me and giving me a squeeze. “You’re a good son. Did I ever tell you how proud I am of you?”

“Probably,” I said.

“Still seeing Sarah?”

I had no idea how to answer, but I didn’t feel any rush from the name. No increased heart rate. Just a feeling of ambivalence. I shrugged.

“It’ll happen when it happens,” she said, confidently.

I wondered about Mark’s life. Not married. Had he ever been? He would have been older than Rachel. In my time, he’d be seventy-two.

Just then Kevin appeared.

“Hey, can you help me carry this?” he asked, as he headed to the old Packard.

I had no idea what he was referring to.

“Yeah,” I said.

There was a footlocker in the back of the car—apparently why we’d gone to Ellsworth. Old military issue, olive drab, with rust along the latches and corners worn to the wood beneath. The kind that creaked open like it had a memory of its own. A faded white stencil barely caught the light: Randall Whitney.

Not Kevin’s stepfather, but the father he never met. Killed in Normandy when Kevin was six months old.

We carried it into the kitchen. Anna placed her hand on the top and went still.

She didn’t say Randall’s name. She didn’t need to.

“I hate war,” she said.

Kevin looked at me. “You have the key.”

And somehow, I did. I reached into my pocket and pulled it out—a small, brass key I didn’t remember acquiring.

I placed the key in the lock, but I hesitated.

I thought about the boy beside me who never knew his father. The woman before me who buried both. And the ghosts who remembered me when I didn’t remember myself.

Anna was watching me. Her eyes wide, glassy with memory. Or recognition.

I gave her the faintest smile. A nod.

And turned the key.

Stephen B. Anthony is the author of Transmigrant, an epic science fiction thriller, available on both Amazon and Audible. The first seven chapters are available on this website for free.

Definitely putting this on my purchase list. This is so well done. Thank you for sharing!