Rook, Authors, and Clue

Plus, Plutarch and Theseus

You never know if stories from your childhood are going to land—or just put people to sleep. I mean, who cares about the early life of Stephen B. Anthony? But then again, people still watch A Christmas Story every year like it’s a sacred ritual. They know Ralphie’s getting that Red Ryder BB gun. They know he’s going to nearly shoot his eye out. And they watch anyway. So yeah—I still believe in nostalgia.

But even if this doesn’t land right, that’s okay. I really write for myself (and my mom, who lurks where I write while she still can — love you, Mom).

Over the last few days, I’ve written about Why I Write, the Great Books, and how my dad deeply influenced my love of reading.

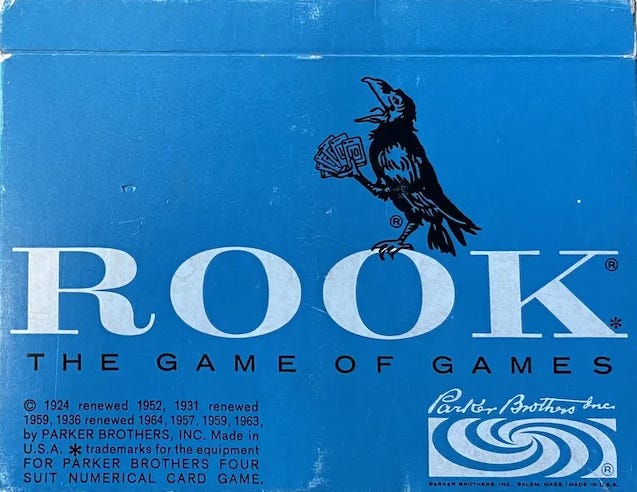

Rook

We were a family that played games together. Some board games, sure—but mostly card games. Parker Brothers decks were regularly spread across our table, and Rook was one of our favorites.

There were a number of ways to score and play Rook, but in our standard game, the cards were ranked 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,1 with a one being the strongest card and highest point value for each colored card suit (red, green, yellow, black). Because the only point cards are 5, 10, 14, and 1, we eventually stopped using the 2,3,4 cards at all, as there wasn’t really a point to them. Removing them shortened each hand by three tricks.

So, it wasn’t uncommon to open a box of rook cards and see a stack of 12 cards unused, still crisply white, while the used cards had dirty edges from grimy hands they had passed through a thousand times.

There were other card games, too: Flinch, Pit, Mille Bornes, and eventually Skip-Bo as it became more popular. Each had its charm.

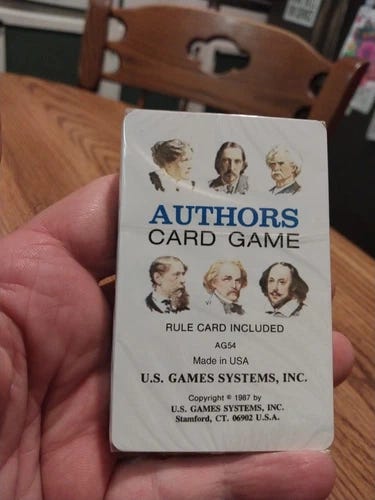

Authors

But my favorite—always—was Authors.

We started playing it when we were really young. It was basically Go Fish, but instead of numbers or suits, each card featured a classic author and a list of their major works. The goal? To collect a full set from a single author—Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and so on.

Without realizing it, we were memorizing the canon.

Learning to associate titles with names. Stories with creators. It wasn’t school. It wasn’t homework. It was just part of how we played.

And I think that’s where it started for me—this sense that books weren’t just words on a page. They were part of life. Part of family. Something to share, remember, and treasure.

So, I found this tonight on eBay and snapped it up. It’s probably 15 years newer than the deck we played with, but it has the same card images and that’s great. Also, it’s brand new in the package, still shrink-wrapped from 1987. The cards have never been touched.

Clue

We played the board game Clue quite a lot. There was Monopoly and others, but Clue was our favorite. In the box, we had sheets and sheets and sheets of checked-off clues from many, many games.

I always wanted to be the yellow token — Colonel Mustard. I also wanted to be the murderer (which may something about my character—see my post on Kannon Niruku for more).

The best was Colonel Mustard, in the Library, with the Revolver.

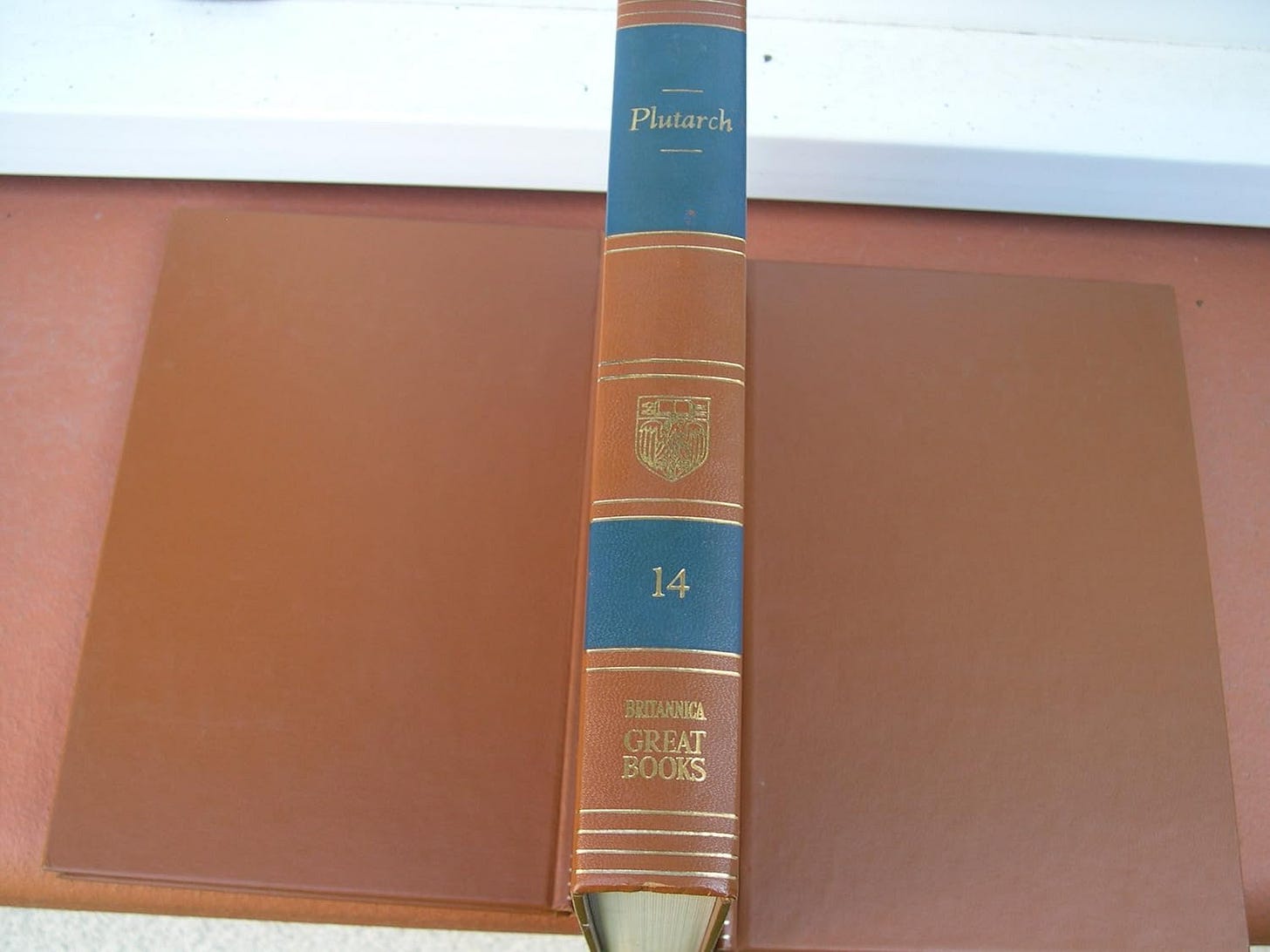

Plutarch

As I wrote in my article about the Great Books, I read every single one of them between the ages of 16 and 21. By 17, I had read up to volume 14.

It was in this volume that I encountered selected Lives from Plutarch—and where I first met Theseus, hero of Athens. He was sent by King Minos into the Labyrinth, constructed by the inventor Daedalus, to contain the monstrous Minotaur. Theseus would likely have died in that maze, had not the king’s daughter, Ariadne, fallen in love with him. To keep him safe, she gave him a ball of yarn, which he unwound behind him as he ventured deeper into the Labyrinth.

After killing the Minotaur, he escaped by following the string back to the entrance.

That ball of yarn was called a clew—and for those of you who know how much I love etymology, you’ve probably already guessed: that’s where we get the modern word clue.

Which, coincidentally, was also the name of one of our favorite board games.

So by 1983, my family had to endure me launching into the origin of the word clue—and the whole Theseus story—every time we opened the game box. It might be why we stopped playing it.

My wife reads this and wonders why I remember this stuff. Why I can recall my first car payment was $257.33, or that my girlfriend’s parents’ license plate in 1978 was 236-101, or that Plutarch is in volume 14 of the Great Books—but somehow forget to stop for milk on the way home.

The truth is, I don’t know either. Maybe memory is like a game of Authors. Some cards stick. Others never even make it into the hand.