ROSIE WOKE TO NEW SNOW.

A fresh, fine powder covered everything. All her tracks along the road had vanished, and she wasn’t completely sure which direction she’d come from. The sky was so overcast that she couldn’t tell the position of the sun.

“What ya lookin’ at?” Dan asked, both hands full of grass, which he kept jabbing into his mouth.

“Dan!” she exclaimed. “I’m glad you’re okay.”

“I’m too quick for wolves,” he said. “What you lookin’ at?”

“The sky,” Rosie said. “I’m not sure which way to go. I can’t remember which direction I was facing when I set up camp.”

“Where are you trying to go?” Dan asked.

“To Grandmother’s house.”

“Ah, well. You go west.”

“Right—but which way is west?”

“I have no idea,” Dan said. “I’m just a hare.”

“A sophisticated hare,” Rosie reminded him.

“True. True,” he mused. He scratched his head, right between the ears, but could not provide an answer.

Rosie packed up her things and extinguished the fire with a minor melody.

At that moment, they heard a loud thud.

Dan skittered behind her feet, hiding .

“What was that?” he asked, whiskers twitching.

They heard it again.

THUNK!

Then another.

THUNK!

The sound continued at an even pace. Rosie followed it, putting fresh tracks in the snow as she wandered along the trail.

A few hundred yards later, she stopped short. A tree crashed down in front of her, landing across the path. She and Dan both jumped back as the boughs of a blue spruce just missed them.

“Whoa!” Rosie shouted.

“Indeed,” said Dan. “That was close.”

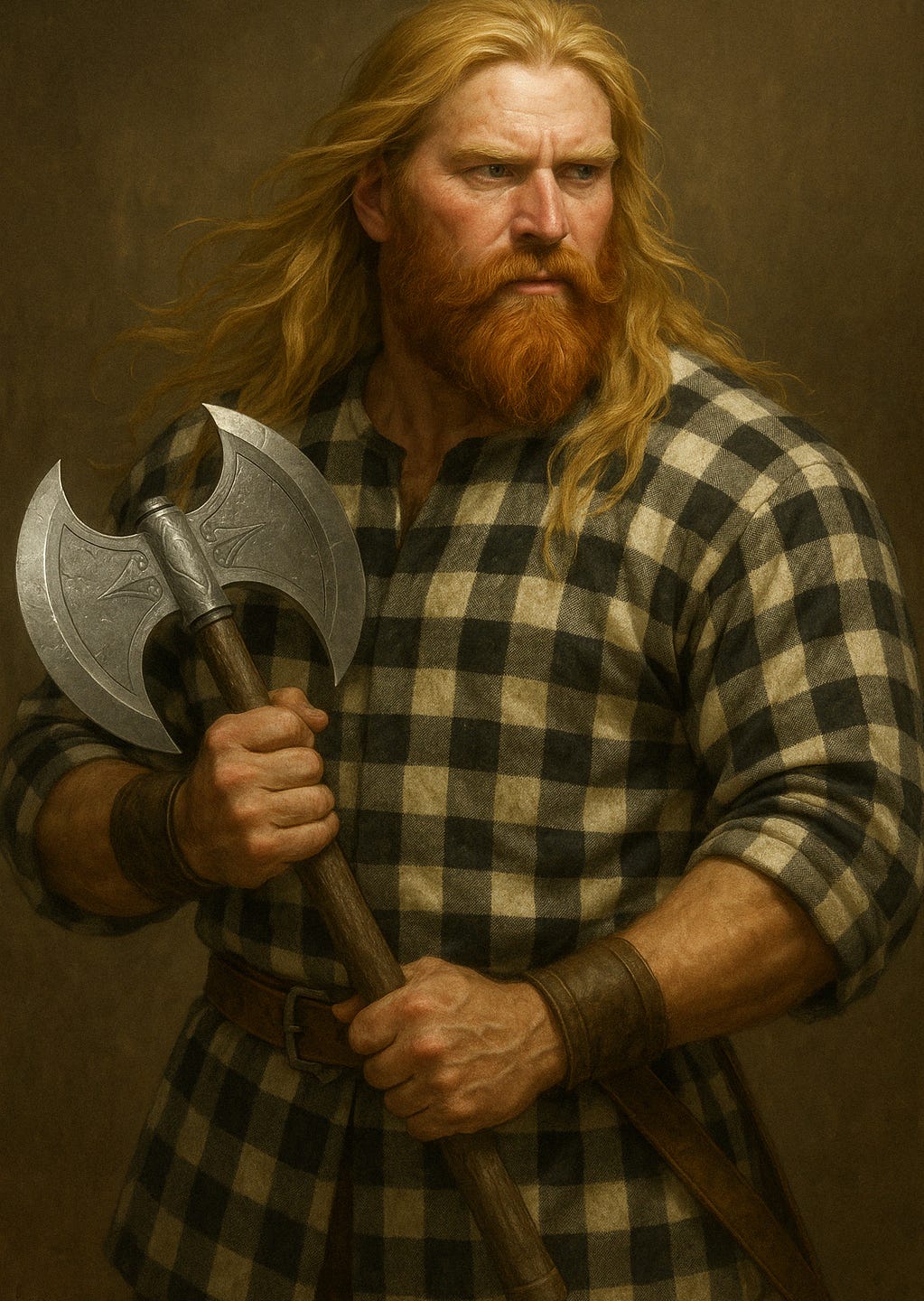

They heard whistling from the forest. Moments later, a man appeared, dragging a toboggan behind him. He was a very large man, with a red beard and flowing blond hair. He wore a flannel shirt—buffalo plaid in white and black—and green pants held up by black suspenders with silver clasps. A wicked-looking silver double-bladed axe rested on his shoulder.

He stopped when he saw Rosie. Dan was likely nearby, but invisible for all practical purposes.

“Top o’ the mornin’,” the man said, nodding.

“Good morning,” she replied.

“Don’t mind me,” he said. “Just cuttin’ some firewood.”

“I thought hardwood was better for fires,” Rosie said, eyeing the spruce.

“It is, mostly—for long burns. But for kindlin’? Sticks and branches don’t split clean. Spruce is ideal for choppin’. Only trouble is the damned needles. Cut you up somethin’ fierce.”

He gave her a closer look. “And who might you be, then?”

“I’m Roselyn.”

“Ah, little Red. I heard you’d be comin’ this way. Now you stick to the trail, hear? Don’t go listenin’ to whispers or wanderin’ near the shadows.”

“What’s in the shadows?”

“Wolf traps,” he said. “There’s a nasty big one been troublin’ these woods since time began. I aim to catch him, see? So stay off the edge—or you’re liable to lose some toes.”

“Wait,” Rosie said. “You heard I’d be coming?”

“Aye, lass. So said your Gramma.”

“You know Grandmother?”

“I do indeed,” he said. “Name’s Karl. I chop trees for her. Bring her firewood. Trap her wolves.”

“So… wolves? Like more than one? How many are there?”

“Just the one, far as I know. But your Gramma’s got a thing for him. Some old dispute.”

“About?”

“Dunno. Maybe he ate her chickens. Wolves’ll do that.”

“Which way to Grandmother’s?”

“West,” he said, pointing.

“Are you going that way?”

“Not anytime soon,” Karl replied. “Still gotta set a few more traps. I’ll catch that growler any day now.”

Rosie was disappointed, but there was nothing for it. She stepped around the fallen tree just as Karl began delimbing it with his axe.

“Thank you, Karl. Hope to see you again,” she said.

“You betcha, lass. Maybe we’ll both make Thanksgiving?”

“That would be wonderful,” Rosie said, smiling. At least now she had a direction.

She had to admit that she felt safer knowing Karl was nearby with his traps set and that big axe on his shoulder. She didn’t wish the wolf harm, really—it was just doing what wolves do—but she couldn’t stand the thought of the creature possibly harming Autumn.

An hour further down the trail, Dan was still with her. He hadn’t wandered off to do hare things yet.

“Begging your pardon, Rosie,” he said, “but I couldn’t help but notice you haven’t been singing at all today.”

“Just didn’t feel like it,” she said. “Sometimes I need to be happy to sing. Or frightened, maybe. Or excited. But right now, I’m just… unhappy. And that doesn’t help me sing.”

“You haven’t even hummed.”

“That’s a good point,” she said.

She stopped to check her basket. Her dwindling goodies were still warm from the music box, which had played softly all night. But it wouldn’t last without music. Normally, she’d wind it again to keep the food company—but today, she was glad to escape it. The tune, which she had heard every day of her life in one form or another, had suddenly grown old.

She closed the basket and looked over at Dan, who was standing on his hind legs, nose twitching.

“Say,” she asked, “you knew that Grandmother’s house was west, right?”

“From where I’m standing, west would be left,” he said.

She shrugged. “But how did you know it was west in the first place?”

“I’m familiar with Grandmother,” Dan said.

“Really? Why haven’t you said so?”

“No particular reason,” Dan replied. “I suppose I was thinking about Twelfth Night. I must say, I’ve enjoyed your singing and humming these last two days—and it occurred to me that I finally understood the first line.”

“‘If music be the food of love’?” she asked.

“Yes, and I think it finishes, ‘play on’—which now means to me that he enjoyed the music and wanted it to continue until he got his fill of love. Right?”

“Yes, I think that’s what it means,” Rosie said, continuing down the road. “Not that I know what it means.”

“Love?”

“I think my parents must have loved me,” Rosie said. “But sometimes I’m not quite sure. Even so, I don’t think that was the kind of love he meant. The kind he wrote about is something I don’t know. At least not yet. But I hope to.”

“Hmmm,” Dan said as he hopped beside her. “You want to be in love?”

“Of course,” Rosie said. “Every person wants that. Really, every person needs that.”

“Well, hares don’t need it,” Dan said.

“Really?” Rosie asked.

“Nope. We’re perfectly content with someone who feeds us, lets us curl up by their fire, and gives us a soft blanket.”

“Is that so?” Rosie said, smirking.

“Indeed,” Dan said, as if settling the matter. “Even so—when you sing, it’s very pleasant to me. And so I think: if music be the food of life, play on.”

“I see,” Rosie said. “You’re saying the singing makes life easier. Or more pleasant.”

“Yes,” Dan said. “That’s what I’m saying, Rosie.”

She nodded, and they walked in silence for a while. Then she began humming. Not singing—just humming. They turned to look at each other and smiled.

(If you’ve never seen a hare smile, please do. They have great smiles—and you can sometimes get them smiling by reading Much Ado About Nothing to them.)

“So,” Rosie said. “Is there no Mrs. Smith?”

“Hares aren’t like that,” Dan replied. “We have several girlfriends in the spring, but we don’t get tied down with all that domestic baggage. We hares are free to do whatever we please the rest of the year.”

“Don’t you ever get lonely?” Rosie asked.

Dan paused, chewing thoughtfully on a blade of grass.

“Sometimes,” he admitted. “But it passes. There’s always something to nibble, something to sniff, a good patch of clover if you’re lucky. Solitude isn’t so bad if you don’t fight it.”

Rosie looked down at the snow beneath her boots, then up at the blank white sky.

“I suppose,” she said. “But I think I’d still rather have someone to walk with.”

Dan glanced up at her, his whiskers twitching.

“Well, you’ve got me for now. And I’m an excellent walker. Very little whining.”

She smiled. “True. You’ve never once complained.”

Dan grinned. Or at least, did something very close to it. “That’s because hares don’t complain. We simply disappear.”

“Please don’t do that,” Rosie said.

He wiggled his nose. “I’ll try not to. Unless I get frightened by wolves or woodcutters."

"Fair enough," Rosie said as they trudged westward.

IT WAS JUST AFTER TWO when they spied him.

A man. dressed in torn rags, lying along the edge of the forest, in the shadows on the south side of the trail.

Rosie caught her breath. There was something familiar about him.

Dan did a disappearing act, and she approached the man cautiously. He looked to be dead.

Rosie had never seen a dead body and she lurched, feeling herself wanting to vomit the bread and peanut butter she had eaten just two hours ago.

She put her hand to her mouth and then stopped suddenly.

He moved.

The man tried to sit up and reach for his leg, but fell back into the snow, breathing heavily.

"Are you okay?" she asked from a distance.

He turned to look at her. The strange eyes, the ears two big, the wide mouth currently in a frown. It was the slightly homely man from early in her trip.

"Help?" he asked.

Stephen B. Anthony is the author of Transmigrant, an epic science fiction thriller, available on both Amazon and Audible. The first seven chapters are available on this website for free.