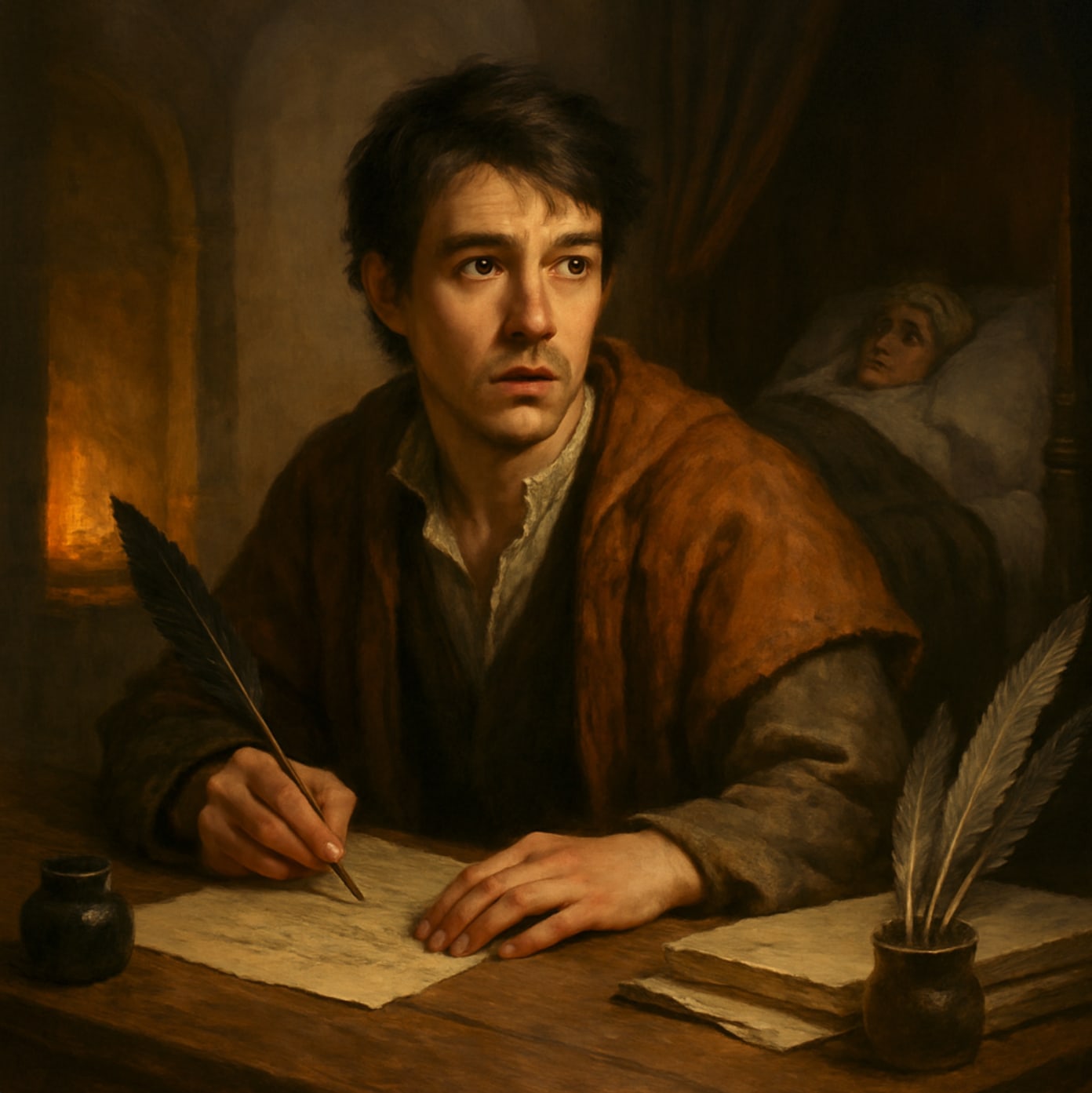

Moses Miller was a scribe of no renown, barely eking out a meager existence from the scraps of the writing table. He had never penned a great work. In truth, he had written nothing interesting at all. So, it was no small wonder when the dying queen summoned him to record her last will and testament.

Honestly, he thought it was a joke. Some fellow scribe from the Academy of the Quill had decided it was funny to send a page to Moses' little hovel demanding that he come see the queen.

It might have been Chenguer, who had bullied him in school, or perhaps Aurelian, who he had roomed with in the first year only to go on and publish thirteen books of poetry, most of which could be found in the Queen's Library.

Undecided on the culprit, Moses responded to the nearest target. He tossed a lump of coal at the boy.

“Begone, cretin! Tell your master ‘Very funny’.”

The nimble boy sidestepped the blackened stone and stood on the stoop with his hand out, looking at him expectantly, if a bit warily.

The creature was expecting a penny for his trouble. It was the standard payment, but Moses was loath to give up his pennies and didn't think one was necessarily owed when the page came bearing a prank.

But he thought better of it and fingered two pence, shining them on his stained housecoat, before offering them to the boy. “I'll tell you what,” he said. “Double payment if you go back and piss in your master's ale before the day is done. Agreed?”

“She doesn't drink ale, milord,” the boy said, eyeing the two pence.

“She?” This confused Moses. There were women writers, of course, but they either became famous or housewives. Very few female writers had become vagabonds, which was a social status Moses tried to avoid but felt up to his knees. “Who is your mistress then, lad?”

“Begging your pardon, milord,” he said, doubling down on the prank. “The queen sent me.”

“You've had your fun then,” Moses said. He tossed a single penny to the boy and slammed the door shut in his face before returning to his desk. He sat in the chair and stared at the ink stains on the fingers of his right hand.

Where had it all gone wrong?

A knock at the door aroused him. There hadn't been two knocks on his door in the same day since—well—ever.

The boy was still on the stoop. “I'm instructed to ask you to gather your things, what you'll need for writing, including parchments, ink, and quills, or whatever else you might need. I'm to wait here until you do that and then accompany you to the keep.”

“You're carrying this a bit far, aren't you?” Moses asked, wondering if he might snatch back the penny from this miscreant.

“Milord,” the boy said, “The queen asked me to do this and to be quiet about it. She's not particularly patient these days, and if I come back empty-handed, it won't likely go well for either of us.”

“How long, exactly, are you going to continue with this little charade?” Moses asked, thinking that it might be time for an ale of his own. He'd been rationing the remnants of his firkin for the last week, but did not have sufficient reserves to get it refilled for another two weeks.

“All I'm saying,” the boy replied, “Is that if I come back without you, guards will come next and they aren't likely to treat you gently.”

Moses looked at the boy as if he had gone mad. Since when were children prone to bouts of insanity? “What's your name, boy?” he asked.

“I'm Kane,” he said, smiling.

“How old are you?”

“Nearly eleven.”

“Well, Kane, the nearly eleven-year-old, let me tell you something. Pages at the keep are upwards of thirteen or fourteen years old. Nobody gets to be a page at the keep at ten years old. That's not how your guild works. So why don't you tell me who really sent you and why?”

“Ten-year-olds get to work at the keep if their mother's work there,” Kane said. “I know the captain of the guard. I think you'd rather see me than him.”

“The queen would never send for me. Nobody ever sends for me,” Moses said. “She doesn't even know who I am.”

“She does though, milord.”

“I wish you'd stop saying that,” Moses said. “I'm not a lord of anything.”

“As you wish,” Kane said. “What should I call you?”

“Just Moses.”

“The queen is expecting you, Mr. Moses. Are you going to grab your stuff?”

“Wait! Are you actually serious?” Moses asked.

“Serious as the plague,” Kane said.

“So why don't you have anything official from the queen then, if she really wants to see me?”

“Told you—she wants it kept quiet.”

“What does she want?”

“How should I know? I'm a ten-year-old.”

Moses eyed him suspiciously. “Somehow, I think you're not a normal ten-year-old when it comes to what you know.”

“You ain't lying',” Kane said.

“So, then you know something?”

“I know lots of things.”

“Tell me,” Moses insisted.

“It'll cost you a shilling.”

“A shilling! Why you little shit—!”

Moses was neither strong nor quick. His attempting punch at Kane's nose found only air as the boy quickly side-stepped the blow. Moses stumbled and fell to his knees, cursing as the boy stood a safe distance away.

“Are you coming, or do I go get the captain?” Kane asked, seemingly unperturbed by the attempted assault.

“You want me to come with you when you've nearly just robbed me?” Moses spat. “I don't think so.”

“Robbed you?” Kane said, appearing insulted. “I would never stoop to that!”

“You want a whole shilling to know why the queen sent for me! That's robbery.”

“My knowledge is mine to keep or sell for whatever price I decide.”

“Well, I'm not buying at that price,” Moses said.

“Suit yourself,” Kane said. “Okay, I'm going to head back now if you're not coming. But the queen won't be happy. Don't say I didn't warn you.”

Moses was still about half convinced that it was a prank and just knew that he was about to be made fun of in the very near future. Refusing a summons from the queen was unthinkable. It was a good prank. For the time being, he played along with it while plotting how he might take revenge.

“Hold on. Hold on,” he said. “Let me gather my things.”

The walk to the keep took longer than Moses remembered. Or perhaps it only felt longer because Kane wouldn’t stop talking.

They passed the weathered chapel, the shuttered scriptorium, and the dry well near the old watchtower, its rope frayed to dust. Garreval, once a busy city, was in a state of disrepair, the roads edged in moss, its towers more memory than fortress now.

“You don’t walk much, do you?” Kane asked, skipping ahead a few paces and then circling back like an overeager dog.

“I walk plenty,” Moses muttered. “Just not uphill. And not to humiliating appointments.”

“You think meeting the queen is humiliating?”

“I think being summoned without explanation by a child with a sharp tongue is,” he said.

Kane grinned. “I have other talents, too.”

“I’m sure.”

As they reached the outer courtyard, the keep loomed above them—less a castle than an aging house of stone, softened by ivy and silence. Its faded banners fluttered, its windows shuttered, its gates open not in welcome, but out of neglect.

Kane bounded up the steps ahead of him. “Try to look grateful. She picked you, after all.”

Moses climbed slower, already regretting every choice that had brought him to this moment. Still, something about the hush of the place—its held breath, its watchful quiet—unnerved him.

The antechamber was quieter and simpler than Moses expected. Stone walls, a high-vaulted ceiling, and a single window spilled pale morning light across a narrow desk beside the fire. Everything felt old—dated—long out of style. And like most things in Garreval, it seemed mostly unused.

It hadn’t always been that way. Two centuries ago, the city had been the heart of magical learning, drawing aspirants from across the known world. But with magic long vanished, the place had fallen into quiet disrepair and dignified neglect.

Not that Moses minded. His own little hovel had once been one of the empty homes no one bothered to occupy. He’d claimed it without challenge. There were no descendants left to dispute his stake.

The room was mostly empty. No guards. No other scribes. Just one woman arranging a stack of parchment with gloved fingers.

She glanced up as Kane entered and bowed slightly. Moses followed, clutching his satchel like a shield.

“This is him?” she asked, not looking at Kane again.

“He’s all we could find, given the… constraints,” Kane replied with an exaggerated shrug.

So much for the queen picking me, Moses thought.

The woman gave no reaction, just motioned to the desk. “Sit. The queen will wake soon.”

Moses hesitated. “And you are?”

“Leona.” She turned to face him fully. She wasn’t old—maybe his age or younger—but her eyes had the kind of stillness that made him feel like a boy again. “I tend the queen. And the words she has left.”

“Well, that’s good,” he said, trying to muster some confidence. “I tend words myself. Or at least I copy them neatly.”

“What have you written?”

“I write the Fifth Margin,” he said, almost defensively.

“I've not heard of it.”

“Well, people scribble in the four margins of a parchment all the time. I think of the Fifth Margin as a place I write other things. Mostly, about the layered history of words and ink. I write reviews on works published by others.”

“Sounds dull,” she said.

“I don't think so,” he said.

“I mean, it doesn't sound all that creative. More like you're reporting on other things.”

“I suppose.”

Leona’s lips twitched. Not quite a smile, not quite approval.

“Then you’ll do,” she said.

Moses looked at the desk again. The parchment was unlike any he’d worked with—thick, almost translucent, and edged with tiny pinprick patterns. The ink beside it shimmered faintly, like oil in water.

“This is palace stock?”

“It’s what the words require,” Leona said.

“I didn’t realize words were so particular.”

“Most aren’t. These will be.”

There was a pause. Moses felt Kane watching him, amused.

“Alright, Kane. You can go,” she said.

The boy nodded and departed without a word.

“I brought my ink,” he said, eyeing the ink bottles on the desk.

“You'll use this,” she said. “It's required for this type of parchment.”

“Okay.”

“You'll have a room here. We'll send couriers to gather your things and bring them here.”

“I'll be staying at the palace?”

“Of course,” she said. “Whenever the queen is awake and speaking, you'll be taking down her words.”

Before Moses could respond, a distant bell tolled once—deep, solemn. Leona turned toward the corridor. “She’ll be stirring. When she speaks, you write. You don’t ask. You don’t edit. You don’t comment.”

Moses raised an eyebrow. “What if it’s nonsense?”

“Then write the nonsense exactly.”

He hesitated again. “Are we preserving her dignity, or her madness?”

“It's not for you to worry about. Just write what she says. Can you do that?”

“I can,” Moses said.

Stephen B. Anthony is the author of Transmigrant, an epic science fiction thriller, available on both Amazon and Audible. The first seven chapters are available on this website for free.

I really love your historical fiction! You should do a historical fiction novel next

Very intriguing beginning. I like the premise of taking notes from the queen even if they are nonsense.

Have to say for me, the first paragraph sort of gave away it was a real summons for the queen, so I didn't buy into the is it a prank or isn't it scheme. But it helped established the characters, so I still enjoyed it.